Balochistan, Pakistan’s restive province, is simmering with tensions that have led to violent outbursts in the resource-rich arid region, bordering Iran. Militant groups in the region have carried out numerous attacks, including Pakistani armed forces, causing multiple casualties. But at the heart of the conflict lies the plight of the Baloch people, says prominent Baloch activist and central committee leader of Baloch Yakjehti Committee (BYC), Dr Sabiha Baloch in an interview with Firstpost’s Bhagyasree Sengupta.

While the mayhem is unfolding, Pakistani security officials have been arresting several Baloch activists. One of them is Dr Mahrang Baloch. Just last year, TIME Magazine included the Baloch human rights activist on the TIME100 Next list for her effort to raise the Baloch plight.

While her activism was celebrated around the world, on March 22, Dr Mahrang Baloch was arrested by the Pakistani authorities during a peaceful sit-in where she was demonstrating against police violence on protesters from the previous day. Several other Baloch human rights defenders were also arrested.

Firstpost initially reached out to Dr Mahrang Baloch for an interview which couldn’t materialise due to Pakistan’s frequent blockade of internet services and her eventual arrest. After four months of scheduling, Firstpost finally got in touch with Dr Sabiha Baloch who shared her views on Pakistan’s ongoing crackdown on Baloch activism and the plight of common people in the region. Edited excerpts:

The plight of the people of Baloch

Q. The year 2025 started with protests in Balochistan over the disappearance of Baloch civilians and activists. Could you please elaborate more on the atrocities people are facing in the region?

Dr Sabiha Baloch: The people of Balochistan are deprived of even the most basic human rights. Every fundamental right is denied, from the right to life to freedom of speech. Despite being a mineral-rich region, over 80 per cent of the population lives in extreme poverty. The literacy rate remains one of the lowest in the country due to widespread poverty and a severe lack of access to schools and higher education.

Uneducated and impoverished, people are simply trying to secure two meals a day. However, when they attempt to raise their voices for their rights, they are abducted, tortured, humiliated, and often killed — their bodies buried in unknown locations. With every right denied, the people’s mandate is ignored. All political voices from within society have either been silenced, forcibly disappeared, or killed.

Balochistan has been transformed into a military zone. Certain areas have turned into complete no-go zones or restricted areas for civilians. In cities such as Mashkay and Awaran, even locals can only enter by presenting their national identity cards. Military checkpoints are scattered along the roads, where Baloch citizens are interrogated daily by non-local army personnel.

The army controls the entire economic structure — from jobs and fishing to local trade. People are forced to pay illegal taxes and face brutal consequences if they resist. Many are tortured, some even killed, with no accountability. Women are harassed and, in some cases, coerced into working for the military. There are horrifying incidents where children are abused, homes are bulldozed, and personal property is seized. Even small agricultural lands are taxed illegally, and those who protest face violent retaliation.

The list of human rights violations committed by the Pakistani army in Balochistan is extensive — far too numerous to cover in a single statement. In summary, in Balochistan, fundamental human rights are nonexistent.

Q. To what extent do people in Balochistan feel discriminated against when they compare their situation to Pakistani citizens from other provinces?

Dr Sabiha Baloch: The Baloch people have long endured systemic racial discrimination, particularly when compared to citizens from other provinces. Whether a Baloch is a student, professional, activist, or worker, the moment they raise their voice or express a grievance, they are quickly labelled as “Ghaddar” (traitor). This weaponization of patriotism has been employed repeatedly to silence dissent and suppress Baloch identity.

Our heroes are erased from official narratives, and our history is omitted from textbooks. Baloch languages — Balochi, Brahui, and others — are ignored in the national curriculum and are often seen as signs of backwardness. Even our cultural identity is under constant attack: wearing traditional Balochi attire in cities like Karachi and Dera Ghazi Khan, both of which have large Baloch populations, can lead to profiling, harassment, or even abduction. These cities, despite their Baloch majority, are not officially part of Balochistan, further marginalizing Baloch identity.

In Karachi, Baloch residents are compelled to notify the police before hosting fellow Baloch guests in their own homes — a deeply invasive and discriminatory practice. Baloch students studying in other provinces often experience racial profiling and surveillance. Reports indicate that they are being monitored, harassed, and even detained under vague suspicions of anti-state activity — simply for being Baloch.

Within Balochistan, discrimination remains equally severe. Citizens are routinely stopped and interrogated at military checkposts. Identification cards are consistently checked, particularly for individuals with Baloch-sounding names or appearances. There have also been alarming instances of soldiers cutting the hair of young boys or altering their wide shalwars — both vital symbols of Baloch identity — as a method of humiliation.

Opportunities for economic development are often denied to locals. In Gwadar, job advertisements for port-related positions have explicitly stated, “Punjab domicile required,” effectively excluding Baloch applicants from employment in their own region. Similarly, in mineral-rich districts like Chaghi, local miners struggle to obtain leases, while outsiders — especially from Punjab — are readily granted them. In Bolan, a green zone of Balochistan ideal for agriculture, Baloch farmers can’t even access urea or essential agricultural inputs, which authorities either hoarded or misallocated.

Moreover, in higher education, the representation of Baloch students is deliberately suppressed. At several universities across Pakistan, the enrollment of Baloch students remains alarmingly low, not due to a lack of qualifications, but because of institutional barriers and discrimination in admissions. The few Baloch students who gain admission to prestigious institutions often encounter a hostile environment where their identity is questioned and their presence resented.

Q. Is there any scope for your group to sit with the Pakistani government and find a middle ground?

Dr Sabiha Baloch: I don’t see much scope, but I do see hope. Peaceful politics has always been suppressed in Balochistan, yet it has never truly failed. Through peaceful means, our people have learned a great deal. Yes, if we continue down this path, our organizations may be banned, and our leaders could be abducted, imprisoned, or even killed. But even under this crackdown, our struggle continues to educate and awaken the nation.

With every step, people gain a deeper understanding of the problem — and knowing the problem is half the victory. The repression we encounter only strengthens our national consciousness and deepens the people’s resentment toward oppression.

So, we hold onto hope — that we will organize our nation and gain the strength to overthrow tyranny through this organization. And even if we do not see immediate results, our peaceful resistance will become a powerful chapter in our history — a foundation of knowledge, experience, and sacrifice that brings future generations closer to victory.

Do the atrocities compel people to take up arms?

Q. Do you think curbing the voices of Baloch activists, in turn, compels militants to take up arms? Why are Pakistani establishments reluctant to hear Baloch’s voices?

Dr Sabiha Baloch: Whenever Baloch political and human rights activists try to raise their voices and express their concerns, not only are they ignored, but the state responds with force as if it has declared war on its own citizens. This has pushed the people toward a more violent path of resistance—a path that, sadly, has become the most powerful and widely accepted form of struggle in Balochistan today.

After years of political activism, even our people mocked us when we chose the path of peaceful resistance. They said, “What will you achieve? You’ll be killed, and no one will care. If you want to be heard, pick up arms — the state only listens to explosions, not your slogans.” Still, we insisted that peaceful resistance is necessary; it is the right path. However, the state’s brutal actions now justify those doubts among the common people. They are beginning to believe that violence must be met with violence — because the state has made it clear that peaceful voices will only be crushed.

The arrest of Dr Mahrang Baloch

Q Dr Mahrang Baloch, who was recognized by Time for activism, was charged and arrested for sedition, what are the authorities accusing her of?

Dr Sabiha Baloch: Even the authorities seem confused about what they are accusing Dr Mahrang of. When she was first arrested, no official documentation was provided. The Deputy Commissioner initially claimed that members of the Baloch Yakjehti Committee (BYC) broke into the civil hospital mortuary and removed the bodies of individuals allegedly involved in the Jafar Express incident.

However, the following day, the same DC released a different statement, indicating that Dr. Mahrang had been detained under Section 3 of the Maintenance of Public Order (3MPO). This inconsistency highlights the state’s lack of transparency and credibility in its actions.

Dr Mahrang and other BYC members have repeatedly faced sedition charges and false FIRs. However, the only justification given this time is that she is being detained “to maintain law and order.” In reality, we believe the state is attempting to silence the voices demanding justice. Dr. Mahrang and the BYC leadership embody the struggle of the people, and the state is trying to force them into compromise through fear and repression.

Q What is the current condition of Dr Mahrang Baloch, are authorities allowing family to visit her?

Dr Sabiha Baloch: Dr Mahrang’s family was unable to meet her for the first three days. It was only after a court order that visitation was granted. Despite being a political detainee, she is not treated as one. When she fell ill, no medical attention was provided until the following day —only after her sister submitted another application to the court requesting a doctor.

Surveillance cameras have been installed in her cell, monitoring her 24 hours a day, denying her any sense of personal space or privacy. The jail superintendent, who reportedly treated her with basic decency, was transferred. In her place, new staff were appointed under the direct influence of the ISI, indicating a clear attempt to tighten control and exert psychological pressure on her.

Pakistan’s hunger for Baloch resources & love affair with China

Q. Do you think that the Pakistani regime is prioritizing the selling of rich natural resources of Balochistan to its foreign allies rather than using them for the good of the local people?

Dr Sabiha Baloch: The life of every single Baloch person screams the truth — that Pakistan is only interested in selling our resources while giving us nothing in return but pain and agony. Our gold is sold for the price of paper, and even then, the revenue doesn’t return to Balochistan. In the most recent agreement between Barrick Gold and the government of Pakistan, Balochistan was promised only 3 per cent of the profit. And even that 3 per cent exists only on paper — in reality, it vanishes into the deep pit of corruption.

We have the largest gas fields in the country, yet the gas is piped directly to Punjab. Aside from parts of Quetta city, the rest of Balochistan lacks access to it. Urban centres may receive a limited supply, but most towns and villages are entirely cut off. Take Chaghi, for instance — a mineral-rich district from which trillions of rupees worth of resources are extracted. Still, there isn’t even a university or a tertiary care hospital for the residents living there.

In Sui, people die from cholera because they don’t even have access to clean drinking water. In Koh-e-Suleman, cancer cases are rising rapidly due to radioactive materials being extracted and irresponsibly disposed of, but there are no hospitals to diagnose or treat these illnesses.

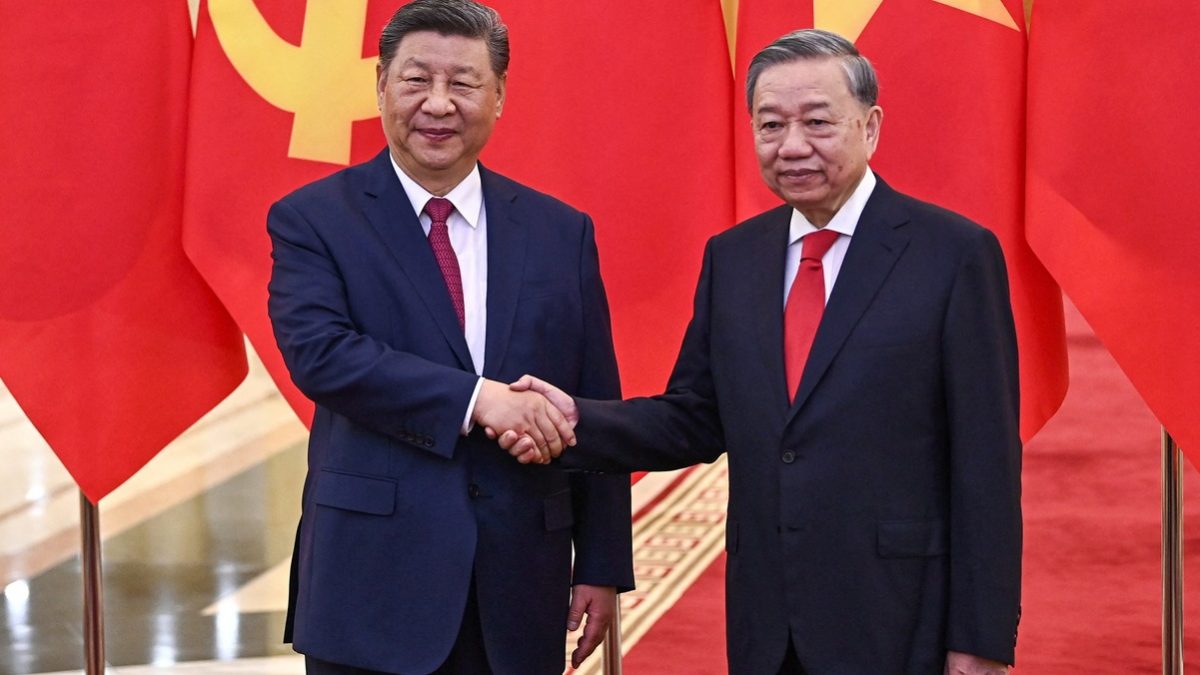

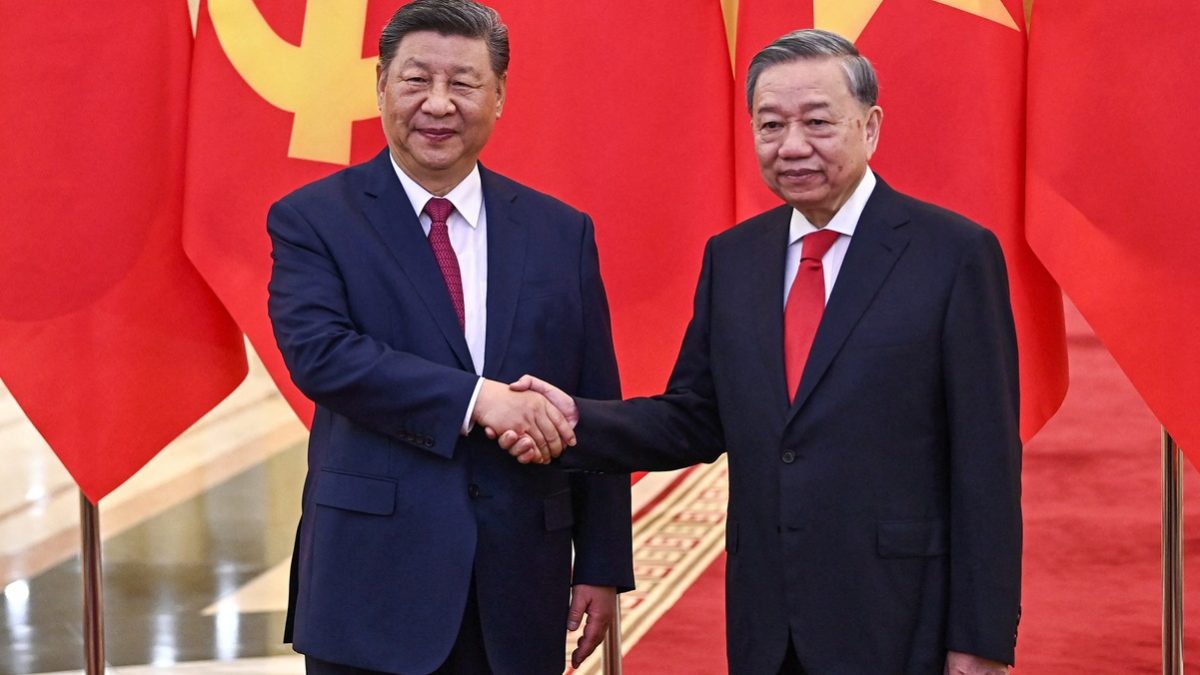

Q. Does Pakistan’s utmost dependence on China come at the cost of the Baloch people? What is the situation on the ground?

Dr Sabiha Baloch: Pakistan’s economy heavily relies on the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) — a project celebrated by the state as a game changer. However, for the people of Balochistan, particularly in Gwadar, this project is nothing less than a tragedy written in blood.

Half of Gwadar has been designated a no-go zone for locals and has transformed into a high-security port area. The remaining population has lost their primary source of livelihood — fishing. Chinese deep-sea trawlers have overfished the coastal waters, leading to the extinction of several fish species and the destruction of the ecosystem that sustained generations of local fishermen. This economic suffocation drives entire communities to leave their ancestral land in search of survival in other cities.

CPEC’s road infrastructure, hailed as progress, has come at the cost of hundreds of Baloch villages being razed. Those who resisted this forced displacement were met with abductions, extrajudicial killings, or forced surrenders. Many were made homeless, left with nothing but grief and silence.

In reality, CPEC is being constructed on the blood, homes, and livelihoods of the Baloch people. While the state enjoys the benefits and prides itself on development, the people of Balochistan continue to pay the price — with their lives, economy, and land.

How the world neglects the Baloch crisis

Q. While the West has been vocal about crises worldwide, some say its leaders or media have said or reported little on Balochistan. Do you think that is the case?

Dr Sabiha Baloch: Yes, this is the painful reality — our voices go unheard, and our struggles remain unreported. I often search for answers within ourselves. Perhaps we’re not professional enough. Perhaps we don’t know how to present our story the “right” way. But then I see global media — BBC, Al Jazeera, and others — highlighting the smallest protests worldwide while we do far more yet remain invisible.

I read an article in Al Jazeera about people showing solidarity with Palestine by organizing an iftar outside a building. However, in Balochistan, families have spent entire months sitting on the roadside, breaking their fasts next to photos of their missing loved ones — yet, no one noticed. No one reported it.

I saw international coverage of an elderly Ukrainian woman who walked miles in search of safety — yet there is silence when elderly Baloch women journey across districts, exhausted and heartbroken, to raise their voices for their missing children.

There are headlines when bookstores are raided in Palestine — but here in Balochistan, not a word is said about the countless raids on bookstalls. In one instance, police destroyed stalls and even’ arrested” over 300 books along with the students selling them. Yet, no international media took notice.

Q Many say what Pakistan is doing in Balochistan is ethnic cleansing of the Baloch people. What is Pakistan gaining out of this, and when will this stop?

Dr Sabiha Baloch: This is the harsh truth: Pakistan is carrying out ethnic cleansing of the Baloch people — and the sole reason is our land and resources. Pakistan doesn’t value the people of Balochistan; it only wants the land beneath our feet and the wealth it holds. The Baloch people are seen as an obstacle to this exploitation — the biggest hurdle in their looting.

Our land’s geographical importance, combined with its long, warm coastline and abundant natural resources, has brought us suffering. The Baloch people have inhabited this land for centuries—long before its strategic and economic value was recognized. We endured harsh weather, limited facilities, and isolation but remained content and deeply connected to our land. And when threatened, we have always stood up to defend it.

A new colonizer has arrived to extract our resources and colonize the land. They aim to dilute our population by bringing in people from other provinces while killing, displacing, and disappearing Baloch people. They are attempting to erase our identity, our culture, and our presence.

Because the geographical importance of Balochistan cannot be physically moved to Punjab, Pakistan is instead trying to remove the Baloch from Balochistan. This is ethnic cleansing — done to clear the way for a resource-rich colony where no resistance remains, and the land can be exploited without question. This systematic ethnic cleansing will only cease either when there are no Baloch left to resist — or when the oppressive structures enabling it no longer exist.

The Baloch Code

Q What is the Baloch code? Can you tell us briefly what it entails and how it looks at minorities like Hindus?

Dr Sabiha Baloch: The Baloch are a multiracial nation, united not by bloodlines but by a shared moral and cultural code—the Baloch Code. This code represents the ethical and social values that bind our society together. Anyone who accepts and practices these values is recognized as Baloch, regardless of their racial or ancestral background.

The Pakistani state promotes the false narrative that certain tribes are “not Baloch.” In reality, being Baloch is not determined by tribal affiliation; it is about living in Baloch society and upholding the values of honour, hospitality, justice, and unity that define us. These values are deeply sociopolitical and intended to create an inclusive society where everyone has a place.

This is why, throughout history, tribes from various parts of the world that settled in Balochistan adopted the Baloch Code and proudly identified as Baloch. Neither the state nor anyone else can assign or take away this identity.

Even religious minorities, such as Hindus and others, have lived with dignity and equality in Baloch society. They maintain their own religious and cultural traditions — their temples, their rituals — yet when asked who they are, they don’t simply say, “I’m Hindu.” They say, “I am a Mengal,” or “I am a Bugti,” aligning themselves with the Baloch tribes and identity.

Before the forced annexation of Kalat State, Hindu families lived peacefully within the castle. This embodied the spirit of Baloch society: inclusive, tolerant, and united.

Today, regrettably, the situation has shifted. The same Hindu communities that once lived in harmony are now experiencing harassment, insecurity, and exclusion — a sign of the broader deterioration of Baloch values under authoritarian rule.

Is it fair to blame India?

Q Pakistan has at times blamed India for the unrest in Balochistan, calling it ’terrorism’. What do you say to that

Dr Sabiha Baloch: Firstly, regarding every sociopolitical issue or problem, Pakistan tends to find fault in its neighbouring countries instead of examining its own weaknesses. Journalists who practice genuine journalism are branded as Indian agents. Similarly, writers who tell the truth are labelled as Indian agents. Politicians who take an independent stance or refuse to back the ruling generals are also called Indian agents. Even when a court makes a ruling against the military, it is swiftly accused of being an Indian court.

This mindset has tainted the thinking of Pakistan’s institutions and think tanks, which now seem to view every issue through the lens of India. Consequently, Pakistan is politically declining day by day. It’s difficult to determine whether this is due to sheer ignorance or willful blindness, but continually blaming India represents Pakistan’s greatest loss. It has entirely paralyzed its capacity for critical thinking and addressing internal issues, making these problems stronger and more complex.

Secondly, when we discuss the issue of Balochistan, since 1948, the Baloch nation has faced state repression, brutality, and barbarism; thousands have been killed, thousands have disappeared forcibly, and the entire nation is a victim of state oppression. When the people raised their voices against this injustice, the state labelled them as Indian agents, but such accusations do not hold weight now because people are aware of and are resisting this injustice.

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)