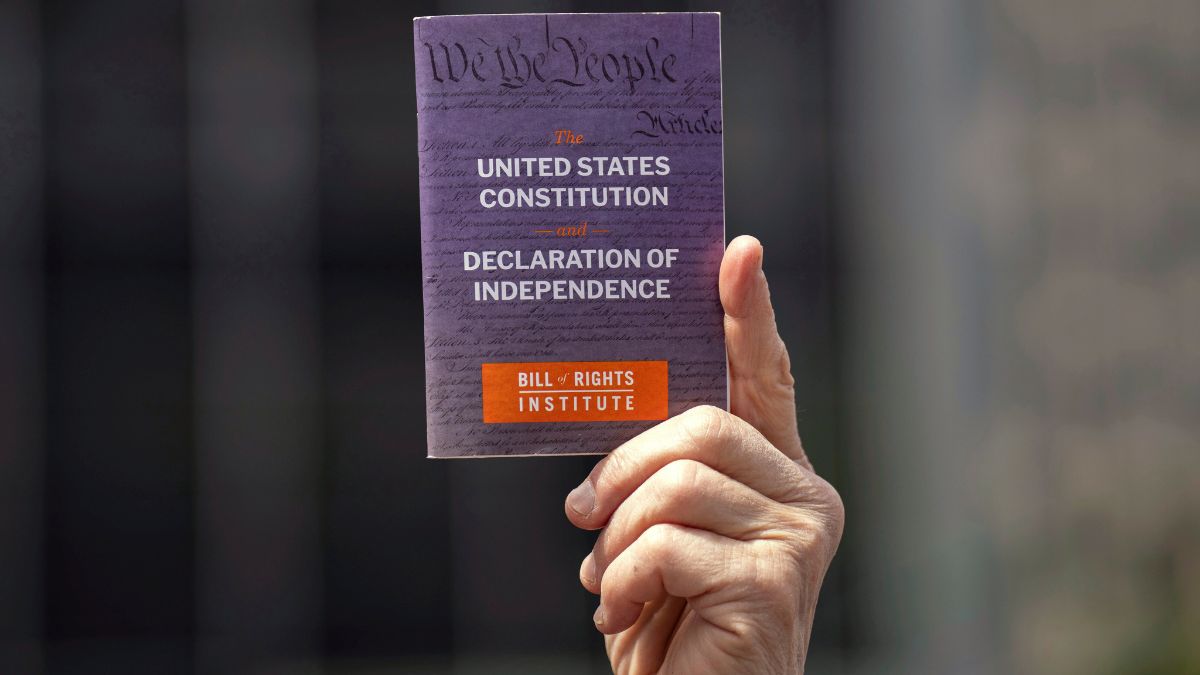

For over two centuries, American democracy has relied on a deliberately constructed system of checks and balances. Though often slow and imperfect, this “elaborate, clunky machine,” as one historian put it, has generally prevented any one branch of government from overpowering the others even under pressure from ambitious presidents.

In recent years, Donald Trump tested this system like never before, issuing sweeping executive orders, slashing agency funding, and openly challenging court rulings. While the constitutional framework has largely held, experts warn its success depends not just on structure but on leaders’ willingness to exercise restraint. Here’s a look at how US democracy has weathered both past and present power struggles.

The genesis of judicial review

The first and most defining assertion of constitutional boundaries came in 1803, with Marbury v. Madison. Outgoing President John Adams had appointed William Marbury as a justice of the peace, but his successor, Thomas Jefferson, and Secretary of State James Madison declined to finalise the commission. When the case reached the Supreme Court, Chief Justice John Marshall ruled that Madison had acted improperly, but also declared the law underpinning the suit unconstitutional. In doing so, Marshall denied the request and established judicial review—the court’s power to strike down congressional laws that exceed constitutional bounds.

Historical challenges to the balance

In 1791, debates raged over Congress’s authority to charter a national bank. Although Alexander Hamilton’s Federalists prevailed, President Andrew Jackson later opposed the bank’s recharter in 1832, vetoing it despite congressional approval. His decision reflected growing populist sentiment against centralised economic control and highlighted the president’s veto power as a significant legislative check.

During the Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln suspended habeas corpus, allowing the detention of individuals without trial. Although this move was later ruled unconstitutional by Chief Justice Roger Taney, Lincoln defended it as necessary to preserve the Union. Congress later retroactively approved his actions, reaffirming the fluidity of executive power in wartime.

Following the war, President Andrew Johnson clashed with Congress over the direction of Reconstruction. While Congress sought punitive measures against the Confederacy and protections for newly freed African Americans, Johnson issued pardons and attempted to curb the Freedmen’s Bureau, emphasising the persistent tug-of-war between legislative vision and executive authority.

Historical tests of executive authority

In the 20th century, new episodes tested the system’s resilience. President Woodrow Wilson’s push to join the League of Nations was ultimately blocked by the Senate, which refused to ratify the Treaty of Versailles over concerns about foreign entanglements. Later, President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s (FDR) New Deal programs met resistance from a conservative Supreme Court. His controversial proposal to expand the court—a move critics called a “court-packing scheme”—failed, but the episode underscored the judiciary’s power to limit sweeping executive reforms.

FDR also broke the two-term precedent, winning four elections during the Great Depression and World War II. His long presidency prompted the passage of the 22nd Amendment, formally capping presidential terms at two—a safeguard against entrenched executive power.

Richard Nixon’s presidency brought a dramatic showdown over executive privilege. After the Watergate scandal exposed efforts to conceal a break-in at Democratic headquarters, the Supreme Court unanimously ordered Nixon to hand over Oval Office recordings. Facing certain impeachment, Nixon resigned, marking one of the most striking enforcements of accountability on a sitting president.

Contemporary challenges under Trump

Donald Trump’s presidency marked one of the most vigorous modern tests of the constitutional order. In his first 100 days, he issued a flurry of executive orders, attempted to dismantle or defund several federal agencies, and publicly undermined judicial decisions that went against his agenda.

In a move emblematic of his expansionist approach to executive power, Trump signed Executive Order 14215 in 2025, aiming to bring independent federal agencies under closer White House control. Critics warned this could politicise institutions historically insulated from partisan influence.

Trump has also raised eyebrows by questioning due process rights. After a Supreme Court decision in 2025 overturned a wrongful deportation, he publicly suggested that not all individuals in the U.S. are entitled to constitutional protections—a position that legal scholars widely criticised as incompatible with the 14th Amendment.

Speculation around Trump seeking a third presidential term, despite the 22nd Amendment, has also stirred debate. Some allies have floated proposals to amend the Constitution, though such an effort would face steep political and procedural hurdles.

The role of public trust

Even as the system endures, it relies heavily on public confidence and the good-faith behaviour of elected officials. Recent surveys show waning trust in all three branches of government. A Gallup poll found that confidence in the judiciary has dropped below 50%—a historic low—while the executive and legislative branches fare even worse.

According to John Carey, a political science professor at Dartmouth College, the system was never meant to be foolproof but was designed with the assumption that officials would occasionally test its limits. “It only works when people restrain themselves from using all the power they technically have,” he said.

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)